With Respect to George Renwick by John Condon

Aug 21, 2022So many memories of George Renwick, spanning half of my life.

A dear friend, a remarkable man, an influence on thousands.

Beginning the very first year George and I met in the 1970s (courtesy of Cliff Clarke) at the Stanford Institute for Intercultural Communication (SIIC) we always made it a practice to spend at least an hour together each summer in peripatetic conversation—talking as we walked together. For decades at the Portland SIIC this was usually walking in some beautiful setting, a nearby park or quiet neighborhood early in the morning before the activities of the day began.

Beginning the very first year George and I met in the 1970s (courtesy of Cliff Clarke) at the Stanford Institute for Intercultural Communication (SIIC) we always made it a practice to spend at least an hour together each summer in peripatetic conversation—talking as we walked together. For decades at the Portland SIIC this was usually walking in some beautiful setting, a nearby park or quiet neighborhood early in the morning before the activities of the day began.

At Stanford our first trip together was to travel up to San Francisco on a Sunday to the Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco, with the now legendary Rev. Cecil Williams whom neither George nor I had heard of then. The church was a place of social activism for social justice. At that time, it was the impact of the introduction of BART, the Bay Area Rapid Transit, and the gentrification that was destroying neighborhoods. Long-time residents could no longer afford to live as the prospect of these new train stations upended property values that destroyed communities. That day George and I began a life-long friendship as we learned a lot about our interests and values in the context a changing urban culture.

I just realized that the most hours together with George were when we first met at Stanford, and then decades later at one of my last times to be with him, just a few years ago. George invited me to where he lived in Carefree, Arizona; he put me up at a local resort complex to enjoy an overnight stay. We talked for an entire day and an evening and the next morning. This was shortly after his sister had died; I was returning from a memorial service in California for my sister. I'll describe some of that conversation below.

George was the best listener I've ever known. When he was with you (he was this way with everyone) you were the center of his attention. He listened, he cared, he was curious and really interested. Friends told me he was this way with their kids, too. Anyone who had attended SIIC in Portland would probably notice George in the evenings, after the workshops had ended (his always ended later than others, and he gave homework!) meeting with one or another of the participants and talking with them for hours. He offered ideas, suggestions (if they were sought), and he was likely to ask more questions, probing further and he was candid in his responses.

I believe that if people who knew George and tried to describe his character they might put "honest" at the top of a list of qualities. In his SIIC workshops for aspiring intercultural communication consultants he discouraged most of the participants by being honest about the prospects of making a living in a profession many idealized.

There is a principle in interpersonal communication theories of the essential link between "relationship" and "content" talk, attributed to Gregory Bateson. George was brilliant in the "content" part of whatever he was engaged in, but in my experience, he always began with and gave serious attention to the "relationship" part. You'd see this in his effort to see things from another person's or group's perspective. What might they be thinking? What might they expect? What do they need? Obviously, this was part of his effectiveness professionally and why so many of us valued his friendship.

Way back when, George was an editor at the innovative Intercultural Press, begun by dear friend and unsung hero who helped launch the intercultural communication, Dave Hoopes. This was in Pittsburgh, where George and Dave (and Sheila Ramsey and Tobi Frank) were based, a nexus of this new field. George was there when the intercultural field was being established in print — maybe hard to imagine in our digital times. In a global culture where what appears in print still carries more authority than the voice that encouraged the print. Though he was an editor at Intercultural Press George wrote little, but his voice was a force in what others wrote.

In the 1980s, I was sometimes a part of "teams" George assembled when he was hosting intercultural communication conferences where he would give a talk in the morning and then people would split up into small groups in breakout rooms. Esso Eastern, for example, brought in mid-level managers and spouses from their offices in Asia and Europe to Houston for several days, perhaps 40-50 attendees and our team of maybe eight. George asked us to arrive two days before the program would begin, and the first day was almost entirely spent on the eight of us getting to know each other, talking about what was going on in our lives, and just getting acquainted and sometimes reacquainted. This created some discomfort for those who wanted to know what is the plan for the program, who is coming, what are we supposed to do? For George, our relationships with each other—even though we'd be facilitating separately—was of primary importance.

George was a storyteller. His workshops were rich in narrative, never with him in the center, but as a means of presenting the context to better understand whatever the subject was, and with the pleasure of a scene well described; and also, to help lead participants to anticipate issues, questions, challenges, etc., before even getting to those.

George was sensitive to metaphor—how others talked and what their interests, personal and not just professional were. I forget the details, but he once told me of a client whose hobby was woodworking, sensitive to different woods and how a gifted woodworker would see and treat the material he was working with on the lathe or workbench. George described to this manager, a CEO, some ways of seeing an intercultural issue in his organization engaging with another from a different cultural background, using the metaphors of different woods, sensitivity to age and the direction of the grain. A subtle and apt analogy speaking in ways that others wouldn’t have imagined. Again, he was sensitive to the relationship—in this case including the relationship of a person who was not just "the CEO" but one who had a whole other life that he loved, when and where he could work with other tools and the beauty he saw and felt far from the office.

During the conversation with George in Carefree I asked him how he felt about the intercultural field that he was such a part of from the beginning and had reviewed in a state-of-the-art study. He recalled that during the late 1960s and into the '70s there was wild optimism that soon there would be an "intercultural specialist" in every organization and company, but that never happened. The naive optimism (not his words) he said was in part because the people in the intercultural field didn't know much about the organizations with which they imagined working. He said (my memory, not his words), "intercultural communication consultants come to companies not knowing much about the organizational and business culture and then ask the company to learn our language (academic terms) so that we can help them?" He was very critical of what had become of the field and tried to steer it to a more realistic base.

George was a naturalist. He was in awe of nature and a serious student of the nature around him. George grew up not far from me in Illinois, but he lived in the mountains outside of Denver when I first came to know him, and later he moved to southern Arizona. He loved the mountains and the desert, and he learned about these natural environments as he had learned about cultural and religious environments. George used to guide friends on tours to the base of the Grand Canyon, encouraging and assisting the reluctant, and all along the way through several geological zones pointing out how the geology and the plants changed, and the relationship between the land and the indigenous communities who knew the land and survived because of that knowledge.

I don't know when that serious interest in the environment began but I believe it was not unrelated to his mother's seriousness about "natural" foods—as in her "real food cookbook”—and his sister's remarkable sensitivity to and apparently brilliant understanding of animals. During our visit in Arizona George gave me a book that Janet Bennett had given him that E.T. (Ned) Hall had given to the SIIC library, The Man Who Listens to Horses. George knew I was writing a book about Ned and his concepts and methods, and vision. Hall drew lessons from animal communication and had a love of horses and equine-human communication. Aware of my many years living in Japan George generously gave me an ikebana book his mother bought in the 1930s when she visited Japan as part of a year of global travel—a story George enjoyed telling. George’s father had offered the girls (George’s aunts), as a high school graduation gift the choice of tuition and expenses for college or traveling the world for a year. The sisters chose travel, clearly the better choice in George’s view. He also pointed out the courage it took for young women to venture into the world on their own, and implied that his mother’s curiosity and insights were an influence on him.

George was in awe of his mother who encountered crossing landscapes, cultures, and spiritual practices. I think “awe” might be an appropriate word, for the environment is also related to his religious—spiritual—perspective. George often spoke of the strengths and commonalities across faith traditions, and he was (if memory serves) the only SIIC faculty member who a few times in our decades of our "meet the SIIC faculty" homilies ("burning issues") who referred to religion. For some in our largely secular faculty, myself included, this caused some discomfort.

There is for me a paradox or irony or maybe it is balance, when I think of George who was so empathetic, such a listener, seriously interested in others in the moment, so "present" in the current vernacular, but yet so private. During the evenings at SIIC when other faculty were relaxing, casually meeting with participants during the social hour, George would be elsewhere, sitting with one who sought his advice.

George who was there for each of those who sought his counsel also worked with major corporations and helped shape major collaborations across cultures (his story of bringing Ford Motors into China, drawing upon a letter a century earlier), and he was committed to the intercultural field and humble when met each new participant who dreamed of a career in the intercultural field. At the same time, he was among the most private of people I have known.

I imagine it is not uncommon to when someone we knew and loved has passed, there will be times we regret failing to ask questions that we think of too late. That must be an inevitable regret in all our lives, I suppose, what we didn’t ask, and sometimes also what we regret that we failed to say to the other. In the sadness of learning that George Renwick has passed, we should be grateful to have known and admired this strong, wise, innovative, and modest gentle man.

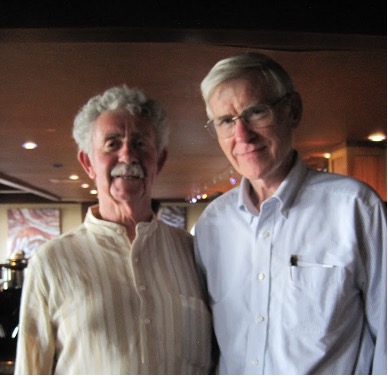

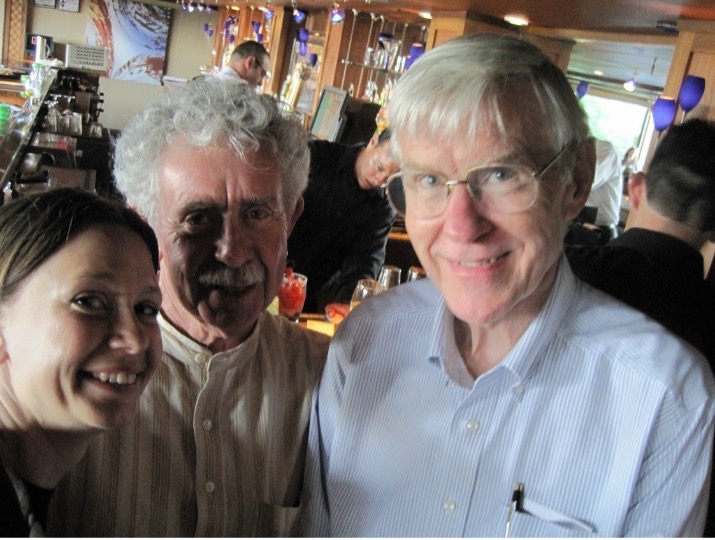

Leslie Weigl, Jack Condon, George Renwick

This picture and the one above were taken by Leslie Weigl